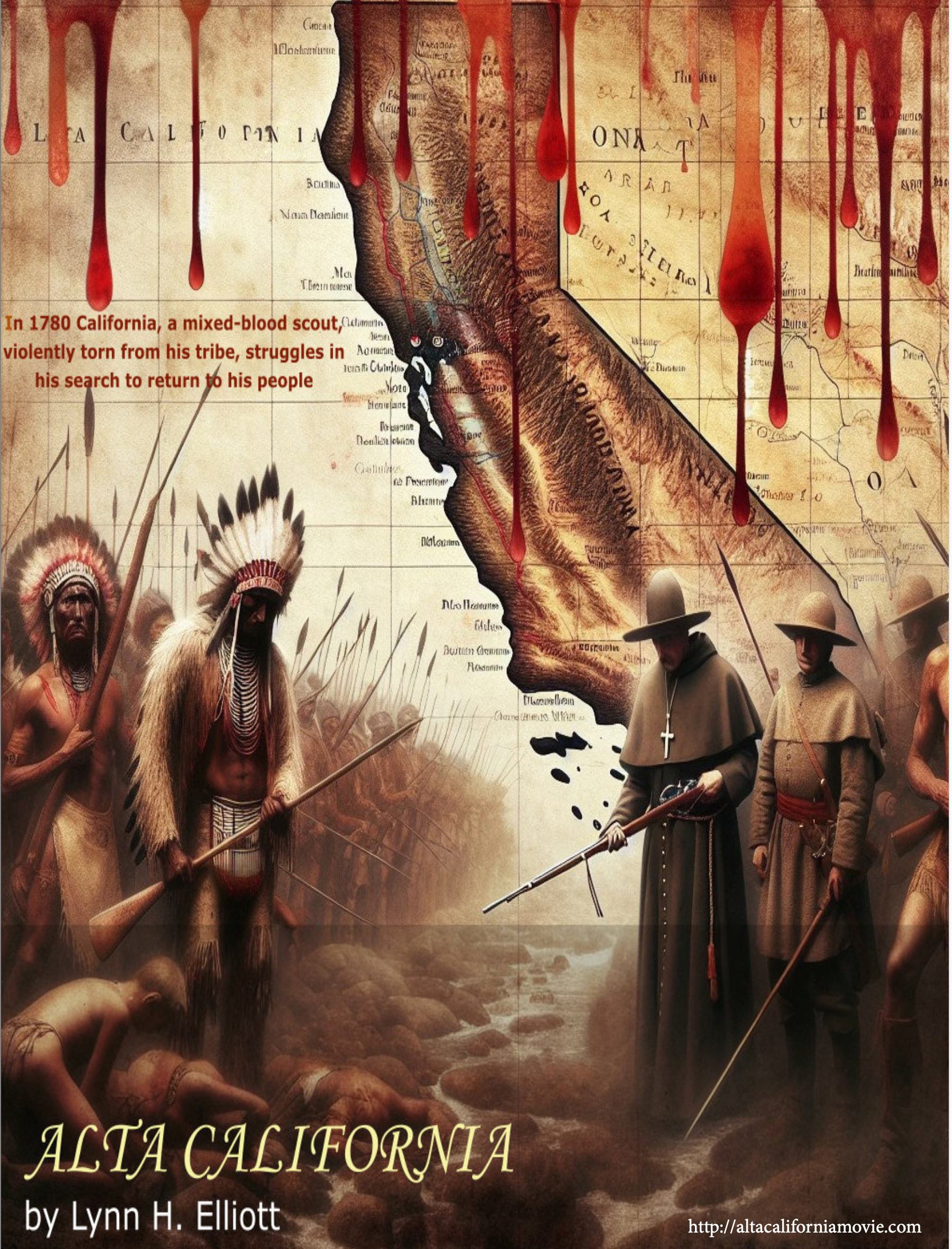

Screenplay : Alta California

Writer : Lynn H. Elliott

Today, we have the pleasure of interviewing Lynn H. Elliott, an award-winning screenwriter, playwright, and masterful storyteller whose work spans across genres and eras. Known for his ability to bring richly layered characters and complex narratives to life, Lynn’s latest project, Alta California, transports us to 1780s California, where a mixed-blood scout embarks on a perilous journey to reunite with his tribe. With a passion for delving into history, identity, and the human condition, Lynn’s screenplays resonate with universal themes that are both timeless and deeply personal. Welcome, Lynn! We’re thrilled to dive into your creative world.

Let’s dive into questions and savor the experiences you’ll be sharing on your journey:

1. Lynn, thank you for taking the time to attend this interview. Your screenplay Alta California is an intense and emotional journey set in 1780 California. Can you tell us a bit about the inspiration behind this story?

I was born in Cardiff, Wales, and now live in California. When I emigrated, I

took a history class wanting to know about my adopted country. My attitude to historical events was fashioned by my British education. History told of wars, power, subjugations, etc. Yet there was none of this in my American history class. It was solely the Constitution and Manifest Destiny. No mention of women, slaves or indigenous peoples. And so began my personal exploration. How many Californian Native American could I name? Five? No. One or two? Maybe. Yet once there were 500+. What happened? What, specifically, about the relationship between indigenous Californians and the “Good Padre,” Junipero Serra?

2. The historical setting of 18th-century California is intriguing. How did you go about researching this time period to bring authenticity to the Screenplay?

I read many scholarly books about the “Mission Era” and soon discovered that Serra’s method of Christianizing and Europeanizing the native peoples often involved brutality and violence. As for the Spanish soldiers themselves, many regarded the natives as no more than animals, not worthy (especially the women) of protecting or converting. (Historians note that native women would “hide in the hills” if they knew Camacho and Cordero were among the Spanish parties.) I soon came across Captain Felipe de Neve, a Spanish nobleman, whose humanistic methods and attitudes to the indigenous peoples were diametrically opposed to those of Serra. His backstory—departure soon after his marriage,dying without ever seeing his wife again—are all true.

3. The central character, a mixed-blood scout, is a complex figure. Can you tell us more about him and what you hoped to convey through his character?

Paco Palido (a fictional character) is a mixed blood since his mother was probably raped by a Spanish soldier. We witness the destruction of his village and slaughter of his mother by Spanish soldiers. He is taken first to a residential school, which are currently under intense investigation. Paco escapes the school, by Neve’s intervention, and becomes of native scout. He differs from the more passive “neophytes” (baptized natives) of the missions. Despite attempts by Serra and Padre Crespi to convert him, Paco, haunted by remembrance of his mother, continues his existential journey in an attempt to discover himself.

4. Your work as a screenwriter and playwright often focuses on deep character studies and powerful dialogue. How does this translate into the narrative of Alta California?

I need to know my characters, good and bad. What are their joys, fears, hates, loves, desires, etc.? The way they convey these emotions is through their dialog. This, dialog, is something I return to time and time again. It has to convey not only thought but emotion. It is not just the what is being said. We must also focus on the how and why of what is being said. “Speak that I may know thee!” And let’s not forget, that silence can often speak louder than words.Serra, for example, is absolutely enraged that Paco Palido, and not him, is invited to visit the Chumash settlement. Serra is tenacious in his desire to convert. Nothing, certainly not this unbaptized savage will take his place. In the third section of the play, we witness, through Paco’s eyes, the actual historical clash between Serra and Neve. With the Spanish leaving California, and the white man coming from the east, the question is: What happens to the neophytes in the mission? Serra is adamant: they stay in the mission where God will protect them. Neve, with the King’s backing, wants them to return to their native habitats and ways. As he journeys around the missions, Paco discovers how determined, how Machiavellian, Serra truly is. His plan will succeed at all costs.

5. The film features repeating of light and movement. What significance do these patterns hold, and how do they contribute to the overall narrative or feeling of the film?

Actually, my background is academic. I began as a professor teaching at a university. I taught no writing classes. That changed when I gained some successes. My teachers were the very playwrights, ancient through contemporary, I was teaching. It was their stories, plots (sequence of events), characters, etc. that guided me as I wrote. After some success as a playwright, I was asked to teach creative writing. Now I had to “study” and teach the very methods I was using and impart them to my students.

6. What advice would you give to aspiring screenwriters and playwrights who are just starting out?

There are a multitude of “How To” books, lectures, seminars, etc. available. All involve spending your hard-earned money. I feel for the young, would-be writer swamped by these “how to” offers. Yet I honestly believe that the greatest teachers are the writers, past and present, who have succeeded. Read Shakespeare, for example, and ask yourself questions. How did he, without any expensive seminars, etc. to guide him, take a story and delve into character motivation, the sequence of events, and so much more that makes a “Hamlet” or “Midsummer Night’s Dream”? Watch a movie and appreciate the clever use of a flashback, editing, etc. Almost as important, if you happen to determine a movie is “bad,” ask yourself why. Don’t just give it a superficial write-off. Explore your dislike in Depth.

7. Considering your extensive experience in both playwriting and screenwriting, how do you decide if a particular story is best told through screenplay?

Actually, I’ve written in a number of forms and “translated” the story into another form. “Pirandello’s Wife” began as a stage play. The “place” is limited, an asylum where Antonietta spent the last 40 years of her life. When I chose to develop it into a screenplay, I was able to move back and forth between the past, her life in Rome, and the present, life in the asylum.

8. In addition to Alta California, you’ve written several other award-winning screenplays. Can you tell us about one or two of your favorite projects and what drew you to those stories?

“Pirandello’s Wife” developed from my teaching Pirandello’s plays. I had, almost flippantly, mentioned a biographical fact: Antonietta was placed in an asylum for the last 40 years of her life. Why? “Gelosia suprema” (excessive jealousy) inherited from her father. Nature was the cause. But what of her lived-life experiences, nurture? And so, in the asylum she attempts to create a drama revealing that her incarceration was wrong (see: https://pirandelloswife.com/). My comedy “Rodeo” was inspired by Ben Jonson’s play “Bartholomew Fayre” (1614). (Ben Jonson’s plays were the focus of my PhD dissertation.). In Jonson’s play, the Fayre itself is not neutral, like hotel. The Fayre, and how people react to it, becomes a character. I asked myself, what would be a contemporary equivalent? A rodeo. People either hate it or love it. The rodeo is a character.

And then there’s my YA novel, “The Boy Who Earned His Magic.” Here, in the Western US, we have a plethora of peoples, languages, myths, and haunting, challenging venues. Why not a YA story bringing all of these together? I’ve since taken the novel and divided into six one-hour teleplay episodes.

9. You’ve written across several genres – historical dramas, contemporary pieces, and even psychological thrillers. How do you approach writing in different genres, and do you have a favorite?

Again, I think of the writers of the past and present. Could MND have been a tragedy? It begins with a father’s threat. Yet Shakespeare chose a comedy. So, the “story” is neutral. It is the writer who challenges him/herself to frame it in a genre. He/she must ask: What form should this story take? Sometimes, the story itself begs a particular genre. A violent man seeks to rectify the death of his father who was betrayed by a “Quisling” could only be a psychological Thriller.

10. With such a wide range of screenplays, do you find yourself using similar themes across your work? If so, what themes do you find yourself returning to most often?

As an immigrant, I love to explore and write, in serious and comic forms, stories of those who, through choice or happenstance, find themselves strangers in a strange land (or even in their own land). I share the immigrants’ attempts to “navigate as safely as possible through an ever-shifting landscape of independent and unpredictable powers” (Alan Jacabs), and the difficulty of coalescing given and adopted values and ways of seeing.

11. With so many successful screenplays under your belt, what’s next for you? Are there any new projects you’re excited about?

I am currently working on two teleplays. My six teleplays based on THE BOY WHO EARNED HIS MAGIC ended with a question: What happened to one of the Jimis? I am answering that question for myself. And then there’s the continuation of my teleplay series, THE SEED-BEARERS. W finished “The Mongrel” with Johnny Z surrounded by those wanting to kill him. What happens next? And, of course, with all of the challenges—critical race theory, male-female relationships, etc.— there is always the possibility of another topic.

12. It sounds like you’re juggling a lot of creative work at once. How do you stay focused and motivated while working on multiple Screenplays?

Interesting question. It’s almost as if—this might sound strange—the particular topic thrusts itself forward, sometimes almost without warning! What did happen to Johnny Z and Jimi? How will Greg, in The Mongrel, respond to his wife protecting Johnny Z? Etc. Then there is revising work. After a valuable critique, I changed the third section of ALTA CALIFORNIA. The focus must be solely on Paco Palido. It is he who is the witness, directly, to the machinations of Padre Serra as he, while seemingly supporting Captain de Neve’s alternative position, undercuts it.

We’re all excited to see the new projects come to life. Thank you so much, Lynn, for sharing your insights and experiences with us. We’re excited to see where Alta California takes audiences!

For further information on ALTA CALIFORNIA, I refer you to my website

(https://altacaliforniamovie.com/) and

short video (https://www.instagram.com/p/Czg7Unhgp4V/)

Got something to share? Reach out to us at [email protected].